The Road Not Taken

“Now which way do you think is the best way out of here?” the older gentleman, in a plaid button down with sleeves rolled up to expose his bony forearms, asked in a thick New England accent. The group he’d brought in with him, particularly his wife, a woman with sharp-cropped silver hair, had no qualms with exposing their origins, going on about how they were coming or going from the Cape and had been planning to stop here all summer. The man made it clear that they were traveling with friends, one in particular with a bad back, who couldn’t handle the bumps in the road.

The question of which side of the road to take comes up a lot. Any day we’re open, the store has more than a few carloads of customers and the state of our dirt road is a topic of casual conversation. The tree-enclosed thoroughfare, picturesque on a sunny day in any season, does possess a fairytale quality, with limbs of maples and white pines hanging across the bumpy path, letting in shimmers of sunlight between the leaves and branches, en route to the hidden treasure that is our beloved Owl Pen.

However, our road, once named Riddell after a family who at one point owned much of the surrounding land, then, through misspellings and over time, changed to Riddle Road, is far less enchanting when you spend each day navigating its bumps and potholes.

In regard to our customers out on a leisurely day trip, we often find ourselves in accord with Robert Frost in recommending the “road not taken.” Like the American poet’s immortalization of his walks through the woods, we recommend the less traversed stretch of dirt and rocks. But this is not for a whim of adventure (though that end of the road is notably steeper with a few blind curves), no, but merely because you’re less likely to blow a tire making your way back to civilization. We want our customers coming and going safely, all Subarus and Priuses intact. However, the questions of navigation do not speak to the larger “riddle” of how to fix the road.

Riddle Road is a public road and not a private driveway. The Town of Greenwich is responsible for its upkeep. During winter snowfall the Highway Department plows and, after a major rainstorm, repairs any washed out sections, removes fallen trees, etc. Generally, this type of maintenance is conducted with sufficient expediency. To answer a question we frequently get, we are rarely, if ever, snowed in up here at the Owl Pen.

That said, the larger, more forward-thinking projects are another story. A dirt road like ours needs to be significantly graded every few years, shaped so that rainwater drains off the sides into ditches. Culverts must be repaired or strategically inserted in spots prone to flooding. Gravel and fill need to be dumped on top and packed in hard to eliminate the dangerous potholes that appear during mud season. Over the three years of our tenure operating Owl Pen, it’s become clear this upkeep, essential for our road, falls below other projects on larger, more traveled roads in terms of priority. Instead, twice a year, once in the spring and once in the fall, some trucks are rolled out to spread some dirt and rocks around to fill gaps or holes. This always reminds me of how my grandfather, whenever we scraped our knees playing out in the backyard as kids, told us to just “rub some dirt on it.” If you know anything about how mud works, then you can imagine just how fast the potholes return. Two or three rainfalls and Riddle Road is a mess once again.

Now you might be saying, “Why don’t you just call the town and tell them to come fix the road?” Well, here, folks, is where we must take that dreaded oft-travelled path into politics. Hey, ‘tis the season!

Sydney and I had been periodically calling Our Man Stan for the last year, leaving polite messages to no avail. You see, Stan is the Town Highway Superintendent, who, incidentally, just happens to live a few roads over and is very rarely able to pay us a visit or respond to our calls. Now, let’s be clear, Our Man Stan is good people. The times we’ve spoken on the phone or when he’s dropped by, we’ve found him to be more than polite and reasonable. Lovely guy. On multiple occasions when we have connected, he’s given assurances that they’d be coming within a few weeks with his road crew, once there was break in the rainy weather or they had completed some project on the other side of town.

On a side note, when we first arrived here Sydney and I had promised ourselves we would become active in the community, and we attended some local political meetings. At one of these meetings, I was asked to perform music at a fundraiser for the new Highway Superintendent candidate in the village of Greenwich. It was there that I first met Our Man Stan. There wasn’t much to his campaign, really. They had the yard signs that read “Vote Our Man Stan.” The whole race seemed to hinge on one argument for electing him over the incumbent, and that was the fact that Stan didn’t have a job. Really, that was the gist of it. The incumbent had a full-time gig working for National Grid while he was Highway Superintending on the side. Unlike that dude, Stan the Man could devote all his time and energy to the job of keeping the roads of Greenwich safe for drivers. That was the pitch to voters. In one of my first brushes with the realities of small-town life, I remember finishing my thirty-minute set of songs at his fundraiser, packing up my guitar and amp, and walking next door to the only restaurant open in the village. When I sat down and ordered a drink at the bar, I began chatting with a woman sitting nearby about how I had just performed at a political benefit next door. She turned out to be the daughter of the incumbent Highway Superintendent. I asked her if she thought the job required someone to not have another job, if it was that time-consuming. She said her father seemed to manage just fine. I asked her if she thought there needed to be political parties involved in this type of position. “Of course not!” was her reply.

Foolishly, when Our Man Stan won the election, I thought that donating my services to his campaign might get us some access, or at the very least bump us up on the list of roads that get plowed first when it snows. No such luck. Our Man Stan keeps things fair.

So this spring when we first opened for the season, after a few calls to Stan hadn’t been returned and the potholes were testing the suspension on our vehicles, we thought we’d take the extra step of calling the town clerk to say that we’d like to place Riddle Road on the agenda for the upcoming Town Council meeting. To our surprise, within an hour or so, we received calls from the head of the Town Council and from Stan the Man himself, informing us that the issue of our road was something he was planning on addressing and there would be no need for us to attend the meeting.

In small towns like ours, word travels fast. It didn’t take long to hear about the drama that had ensued at that meeting we didn’t attend. Apparently, a neighbor from the opposite end of Riddle had come to make a stink and let it be known that Stan and his crew had been neglecting them for years, and if they had no plans of widening and grading the road that a group of long-term residents were prepared to get out there and do it themselves. Our Man Stan pointed out that if they touched the road, they’d be breaking the law. (This is true. You can receive a severe fine. I had to talk one neighbor down our way out of digging his own culvert.) This didn’t go over too well, and things got heated and it nearly came to fisticuffs under the fluorescent lights of the town office meeting room. From a reliable source, I heard the men had to be held back from one another, but eventually a truce was called, peace was made, and the two shook hands. The understanding, as we were later informed, was that Stan had the budget and manpower for two major dirt-road projects this year, and one of them would be Riddle Road. This gave us hope.

I think it must be said here that violence, political or otherwise, is never the answer to any problem. But this near fistfight at the town council meeting apparently helped set things in motion. Almost immediately Stan and his crew came by and did their initial pass of dumping dirt over the potholes on our end of Riddle, and within a month some heavier reconstruction and grading began on the other end. We could tell this was happening because one day we woke to find a number of rollers, excavators, and trucks parked in a clearing on our property just up from the Owl Pen parking lot. No dudes in hard hats or neon orange vests appeared knocking at our door to let us know. But to be honest, we were just so happy to have Our Man Stan taking this much of an interest in our road that we kept our mouths shut.

Just before these construction vehicles mysteriously appeared, Stan had paid us a visit to confirm his plans for the spring and summer. I remember him asking us if it would be okay if he cut some skinny trees in the right of way along the road on our property. Of course we told him that was fine. Anything he had to do to get the road in better shape was fine by us. He was relieved to hear it. He explained that a few of our neighbors down the way had given him hell about moving dirt and stones from the side of the road that was technically their property. That seemed nuts to us, and he agreed. It’s as if these older residents wanted progress but didn’t want anything to change. He said there were others in that direction that wanted their section of the road paved in order to have mail delivered, but that they didn’t understand even if there was money in the budget for that, the road isn’t wide enough, and his crew would have to take out some of those 200-year-old historic stone walls to make room. None of the older folks were going to advocate for more taxes to pay for the project and again, people don’t want to change anything. All of this to say, Stan was doing what he could with what he had. No matter what he did, no one was going to be happy.

This was the same case for his predecessor, and before that, his father Stan Senior. Oh yeah, Our Man Stan is not the first in his family line to be Greenwich Highway Superintendent. Our friend Edie Brown, the previous owner of the Owl Pen, told us that her husband Hank used to have harsh words with the original Stan over the phone on a regular basis. I’ve been told by reliable neighbors that Hank was one tough son of a bitch even well into his 80s and I wonder if, back in the day, the published botanist/Skidmore professor/used bookseller ever had to duke it out with Old Man Stan to get Riddle Road graded.

Trusted sources have confirmed that Hank and the original owner Barbara Probst both fought petitioned movements by residents to pave Riddle Road over the years. Just chatting with the neighbors about the recent road work, we can sense there’s still a small contingent of folks wishing the town would lay some black top over Riddle. Our personal arguments against the idea are clear: the lack of funding, the logistical nightmare of the task, and most importantly to us, how it would diminish the charming remoteness of our literally off-the-beaten-path bookstore. So that leaves us back at square one, dependent on the town for the regular upkeep and repair of our road. That leaves us with Our Man Stan.

After the rollers, excavators, and trucks were used to work on the far side of Riddle Road toward Route 49, they sat on our property for nearly two months over the summer. Each morning, we kept hoping to wake to find Stan and his crew out using all that equipment to tackle the rest of the road, the side most Owl Pen customers come down to get to us from Christie Road. But instead, one day we woke to find all the machines gone.

That is …all but one roller. It sits alone in a field adjacent to the store. It’s not obtrusive in any way, and most customers would miss it if they weren’t looking with a discerning eye. Even after the town’s semi-annual dirt dump in late September, the roller remained.

I like to think Our Man Stan left it as a promise not only that he’ll be back one day, but as a promise that we’ll be on his mind. And to me, that’s a promise that government still works in this country, even when it’s in dire need of more tax-dollar funding. Because come winter, Stan will be out early with his crew plowing every town road equally regardless of whether the people who live on them voted for him in the last election, or even if they tried to sock him in the face at a town meeting. As we all understand, this requires a certain level of trust in our imperfect union and our seemingly, at times, broken system. It’s a faith in the road less taken.

This August we had an unprecedented storm come through that had made its way up from the hurricanes in the south, with extremely high winds and buckets of rain for hours. Part of our driveway washed out, our cellar flooded, and of course so did parts of Riddle Road. An entire chunk of earth surrounding a culvert across from Owl Pen had collapsed, leaving a pit that any driver, especially at night, could have rolled into, causing a severe accident. I placed a garbage can out in front of the ditch. Sydney emailed Stan immediately that afternoon. He didn’t respond. But by the next morning a crew arrived and had the hole filled within a few hours. And that gives us hope.

Essay de Nécessité

I must start off with a disclaimer. This is not an essay for the niminy-piminy puritanical prig. If you are averse to honest descriptions of bodily excretions or the foul messes of grown adults, please click away from here now. However, with that said, like most bowel movements, the following piece of writing is both urgent and necessary. Nature is calling. And just as it quite often does, nature stinks.

Over two years ago now, when Sydney and I decided to leave Los Angeles for the cow-speckled hills of Washington County, NY, to operate the Owl Pen, we had unsullied visions of buying, sorting, and selling antiquarian books and ephemera to loyal local customers and adventuresome collectors vacationing upstate. We imagined there would be dust and cobwebs to clear off some of our product. Occasionally we’d have to dispose of some mousey critters before they made comfy homes of our shelves. We’d enlist the help of a barn cat and a trusty hound-like puppy and the world would look like some animated Disney film our five-year old daughter would watch, where animals talk to one another and sing songs, and no creatures ever get killed, and no character, however true to life, ever seems to defecate. Don’t get me wrong, we had owned pets back in Los Angeles, and assumed we’d be cleaning up after them, placing their partially solid waste in biodegradable plastic bags. We did not expect, however, to be doing the same for our customers.

The former owner, Edie Brown, a now trusted friend and consultant on all aspects of the store’s operation, had advised us before opening for our first season to invest in a composting toilet. Edie and her late husband Hank had run the Owl Pen and had been custodians of its customer bathroom—the Chalet de Nécessité—for thirty years. The original owner, Barbara Probst, who opened the store in 1960, believed enough wayward souls would be wandering up to her book barn to browse the stacks for hours, that she must provide them with some civilized place to relieve themselves. So she had a pre-built ten-by-twelve shed trucked in and set on a concrete slab to be the store restroom. Only slightly more dignified than a typical outhouse, the Chalet had a plywood wall running through that made for a private stall where one could do their business in what was essentially a metal bucket complete with a seat for keeping them from falling in. A pail filled with water was at the opposite side of the shed where one could was their hands after, to complete the rustic experience. Edie told us every week or so for years she’d have to carry this rusty bucket out to a hole Hank had dug behind the store to empty the putrid waste of customers. There were a few reasons she wanted to retire and sell us the Owl Pen, but this had to be on the list of things for which she’d grown tired. Her advice came from experience. “You should get one of those new composting toilets.”

So we did.

Sydney did her online research and picked the top-rated outdoor composting throne. The price was a bit steep at $1000. We thought, of all things, this was a necessary investment—only the best for our customers. It wasn’t long before we began to regret our purchase.

Our handyman Dan helped us install the drain pipe that ran out the back of the toilet through the wall of the Chalet into the ground. A few feet below the earth, a submerged stream of customer’s pee would run, permeating the ground surrounding the structure. At least, that was what we hoped would happen.

We should have known we were in for trouble on our first opening weekend, when one of our loyal customers, an elderly gentleman with a metal walker, the kind with tennis balls on the foot of each leg, returned from a trip to the chalet with the look of a child who knows they did something wrong but attempts to hide their guilt in fear of a reprimand. “That’s some complicated toilet you have there!” he said with a nervous chuckle, rolling his eyes. I decided to check and see what had or hadn’t happened. Just as I’d suspected, he had peed all over the floor, smeared excrement on the seat, and left a big fat turd on the plastic trap covering the hole in the toilet tank.

It didn’t take long to intuit when the Chalet needed to be cleaned. A person would come out looking dazed, bewildered, with a slight hint of concern that would fade from their face as they found their way back to the stacks to browse. The job became for us to find a way to discreetly dart out to the Chalet to clean up after the customer, so as not to embarrass them. Over time, this would become increasingly difficult.

Weeks and months passed, and these fowl occurrences continued regularly and we began to ask ourselves three questions.

The first was “Why is it so difficult for people to figure out how to use this toilet?” This was easily answered. The toilet was designed poorly. In order to open the trap where all of the waste should have gone, one needed to sit on the seat. The pressure from a fully committed tush was necessary to avoid a mess. Now any grown adult of a certain social class could tell you that at least half the human race will not place their exposed buttocks on a public restroom toilet seat. Not to generalize, but let’s face it, many mothers teach their daughters to hover over the bowl starting from a young age.

Another issue with this piss-poor potty was that it required men to sit to pee. This didn’t seem like too much of an ask for the two or three dudes who used the Chalet on any given day. However, the place for the men’s business was located at the front of the bowl, where many of our patrons, both men and women, would accidentally leave used toilet paper, clogging the drain. This was due to the aforementioned seat issue. If one did not sit on the throne, there was no other place to discard the paper.

After a few weeks of frequent cleanings consisting of mopping up urine from the floor, pulling used TP from the drain, and wiping off poop from the whole contraption, we decided to post more signs. We thought, if customers could see specific instructions on every wall of the bathroom, surely that would solve our problem.

The second question seemed a simpler one, possibly one of ethical concerns. And that was, “Why would anyone who comes to our bookstore, a person of such refined taste, extremely literate, with such a degree of intellect, think it completely acceptable to leave their fecal matter splattered about the Chalet de Nécessité?” Yes, it’s a glorified outhouse, but we take pride in keeping it clean. We provide paper towels and hand soap alongside a portable sink that must be filled with water every few days. On the little table that holds these items, beside the covered garbage can, are some bottles of cleaning products that no one has ever thought to use. Though it gets used on average about three to five times a day, the Chalet is often treated like a Penn Station restroom. This conundrum is a dangerous rabbit hole to go down because in the extreme it can lead to a complete dissolution of any faith in humanity, and at the very least turn one into a bitter curmudgeon of a bookshop owner. Best to reckon with mysteries more easily resolved, like, say, quantum mechanics.

The third thought came hard and fast like nature’s call. We have a six-year-old daughter and we live at least a good fifteen to twenty minute drive away from civilization, so a common things we find ourselves saying is “Did you go potty? You should go before we leave.” If we’re headed out on longer excursion, “Are you sure? You’re sure you don’t have to? You should try. We’re not stopping anywhere.” One would think most full-grown adults would ask themselves similar questions…. Especially if they were on a day trip to the Washington County countryside.

Barbara Probst used to tell Edie and Hank that it must be the bumpy ride down the unpaved Riddle Road that set customers’ bowels in motion. We considered that a possible answer. We also thought maybe it was simply the time of day, when the late-morning coffee from brunch at Lakeside General Store had taken effect. But they were only open on weekends, so that wouldn’t explain the blowing up of the Chalet during business hours on Wednesdays or Thursdays. It took some research but we finally discovered a theory that explained the source of our woes: The Mariko Aoki phenomenon.

For those of you unfamiliar, the Mariko Aoki phenomenon is the Japanese expression used to refer to what is, apparently, a common but—for obvious reasons—seldom-discussed problem, “the sudden urge some people feel to empty their bowels when in a bookstore.” We know that if this is the first you’re hearing of this reference, you’re already skeptical. We assure you. It is a real thing. In 1985 a woman named Mariko Aoki wrote a letter published in a Japanese literary magazine describing the effect that bookstores had on her bowels. The magazine was inundated with responses from readers claiming to have had the same experience, and felt obliged to publish a fourteen-page article on the phenomenon in its next issue. And so, a twenty-nine-year-old woman from Tokyo became the name of the condition that plagues many of our customers and causes such considerable grief for weary bathroom attendants.

The science is still out on the reason behind the phenomenon. Is it the smell of the paper and ink that triggers the intestines? Or is it possibly some Pavlovian response to being surrounded by books for those who routinely read on the toilet? Whatever the explanation, one thing is for sure, and that is that Barbara Probst, a woman who had such a sense of humor as to open a bookstore in a barn amidst a forest and name its bathroom the Chalet de Nécessité, would get a kick out of the whole idea. She might have a good laugh about our outhouse ordeals too.

On an overcast afternoon in late July of this year, I was sitting in the house when Sydney texted me while working in the store. “I think some hipster kid just tried to use the Chalet!” My reaction, fueled by both fear and rage, was swift. In less than thirty seconds I darted outside and was standing in front of the Chalet. The door was wide open and I could see the young bearded gentleman on the floor with a roll of paper towels attempting to mop up the floor.

Just the day before, our thousand-dollar compostable toilet had started giving us problems again. What we thought was just more of the same misuse by customers who could not follow the clearly written signs, I discovered was actually a leak at the drain pipe at the back of the pot. A trickle of urine had turned to a puddle and spread to the entryway of the Chalet. We needed a day to once again clean up the mess, and fix the pipe. As the designated sign-maker, Sydney had drawn up a sign to post on the door:

So there I stood looking down at the young twenty-something, while his girlfriend stood behind me holding a tote bag full of books she had just purchased. Both of us seemed to feel bad for the poor guy. He wouldn’t look me in the eye when I asked him, “So you read the sign, right?” He nodded without looking up. “But you used the toilet anyway?” He softly grunted a half-swallowed “uh huh.” I responded with an incredulous shake of my head, stood for a moment, let out a long sigh, and walked away.

The interaction had been so embarrassing the young man hurried with his girlfriend to their car and left a stack of sci-fi paperbacks on the check-out table back in the store. I might’ve felt bad for a minute but then I thought, whatever trauma the guy had suffered, I was the one left to clean up the rest of his pee. After this incident, we gave up on the compostable toilet.

We’ve since acquired a new toilet for the Chalet. It cost two hundred dollars. This one has a more efficient design. The instructions are easy to follow. There’s only one hole for all bodily waste. There’s a button to push to flush all said waste into said hole. It’s simple. This doesn’t mean it’s perfect. Men can now stand up and pee. That, as many women know, causes its own issues in regards to cleaning, but eliminates confusion. The top half of the new potty needs to be filled with water every few days for flushing, while the bottom half needs to be emptied at least once a week. As I did even with the previous fancier toilet, I will have to drag it out to the covered hole towards the edge of the woods behind the store to dump it and hose it out, just like my predecessors did with their bucket. This will be a regular chore, for six months out of the year, for the rest of my foreseeable life. And it will be necessary for me to be at peace with that reality.

In light of all of this potty talk, I’d like to leave you with one last thought ahead of 2024, a year fixing to be as bumpy as our own Riddle Road.

There are certain inevitable forces that come from both without and within us. We must remind ourselves that we feel the same pressures. We all feel them in our guts wherever we are at any given moment. Sometimes we are Mariko Aoki, suddenly struck while browsing the aisles, other times we are the book barn owners carrying buckets of shit to the edge of eternity. Whoever we might be, we must do our business. The responsibility we have to each other is to remember, as humans, we share so many things, one of them being a bathroom.

We here at Owl Pen Books wish you the happiest new year and we look forward to seeing and hearing from you all in 2024.

Handy Man Special

My wife Sydney, whenever we are out at a dinner party, a backyard bbq, or amongst friends anywhere, loves to tell the story of when I attempted to hang a shelf. This was back when we were first dating. I was renting a room in an apartment in West Los Angeles with a few other broke and directionless twenty-somethings. To liven the place up a bit, Sydney thought I should have a little bookshelf above the tiny desk beside my bed. Early on in our relationship, I learned to defer to her opinion on visual aesthetics. She seemed to be my director of interior design well before we even lived together. So I went to Ikea, bought a simple shelf kit, and brought it home without looking at any directions. I drilled into the wall, and quickly, within minutes, installed the cheap grayly painted shelf. Just moments after, while I was placing a few self-help paperbacks, the shelf collapsed, leaving a gaping hole in the wall and a dusty pile of sheet rock on my desk.

Sydney loves to tell this story. She relishes it. Typically, the conversational context lies within home improvement and renovation, which has often been a topic of discussion since we purchased a barn bookstore and a two hundred-year-old farmhouse. So yes, all those years ago, I might not have been able to find the stud to drill into, but Sydney definitely found hers, and unfortunately for her, he was not handy.

I tell you this little story because, in the end, stories seem to be all we have, for better or for worse. What I mean is that I've spent much of my adult life telling myself stories. That might suggest I've been lying to myself, alluding to an outdated colloquial expression of "telling stories." But that's not my intention. I'm referring to the more common literal definition of the word “stories” as a collection of narratives. In the broader context of folklore or mythology, these stories have been passed down through culture, community, and family, to be told repeatedly, often enough that whether their veracity has ever been proven, they are accepted widely as truth. Within the scope of modern social psychology, individuals of all genders, races, and classes tell themselves stories based on the nurture (or lack thereof) of their environment. Through this lens I can see that many of my storied beliefs have helped me achieve much more than I could've ever dreamt, while others have held me back considerably. Here's an example of the latter:

I am not "handy." I've never been good with a hammer and a nail. Drill bits, lug nuts, wrenches, and screwdrivers do not naturally fit in my hands. Tape measurers crackle and shrink, flailing like uncontrollable snakes while I run them along a wall or the back of an armoire. If the old carpenter's dictum is "measure twice, cut once," then mine is something like, "measure thrice and cut as many times as it takes … but never with a power saw… because those are terrifying." All of my inept capabilities and fears surrounding these tasks are not unexplainable. My father, though he had a workbench in the basement of our house growing up, could never be found tinkering away in the wood shop, sawing, and sanding, and therefore passed no knowledge or skills down to me on that front. He preferred to be outside mowing the lawn. But even the basics of lawn care weren’t shared with me. I wasn't allowed to touch the push mower until I was twelve years old for fear I might hurt myself. I was told to read a book, ride a bike, throw a ball to myself in the front yard, practice my saxophone, or watch TV.

Another reason I never learned the artful trait of handiness was that I didn't live in a place like where I live now, where it feels like everyone and their mother knows how to do a basic amount of plumbing and electrical work in their own homes. When you live out in the country where your neighbor is a mile down the road, and the nearest substantial town is at least forty minutes by car, these skills can be crucial to survival. No plumber is driving out to you within a day to fix a toilet. You're lucky if the fire department gets to you fast enough to stop your barn from burning. It's good to know your neighbors for many reasons. As I said, they all know how to do some form of home repair. Many could be employed full-time as professional carpenters. I see a college-accredited forester who told me he built his and his mother's houses. You know… just because he could.

Quite a few people have those types of stories in these parts. Barbara Probst, the fearless creator of Owl Pen, was one.

Did Barbara, a city girl and member of the editorial staff at Mademoiselle magazine, desert Manhattan for the Washington County countryside believing she was someone naturally inclined to raise chickens? There isn't much mentioned in her memoirs that points to any early experience farming. In fact, in an early draft of an article written about Owl Pen Books found amidst her papers which she so graciously left for us to comb through, a writer named Robert H. Mellon points out her determination to become a farmer despite her greenishness. Here he describes her initial months and years after purchasing what she called her “12 acre challenge” complete with a dilapidated farmhouse built in the 1830s and a few outbuildings of the same character and condition:

Having bought the place, a way of earning a living presented a problem, though not for long. Barbara quickly eliminated this obstacle by reading some books on farming and hiring out as a migrant to pick potatoes for local farmers…

…Undaunted, a few months later she plunged headlong into the chicken business when she bought six hens. “I didn’t know anything about chickens,” Barbara said. “I thought eggs came in boxes at Gristle’s. It didn’t matter though, because I love animals. There’s no character in a beet, but I have a lot of affection for anything that squeaks, moos, hisses or groans.

Did Barbara consider herself "handy"? We can't know, but we can be sure that as an independent woman at such a time in 1940s-50s America, she was probably told many stories about what she could and could not do with her life. We do have testimony of her initial ignorance about renovating the farmhouse in 1945, fifteen years before the creation of Owl Pen Books. She kept a detailed record of her work on each room of the house we now live in. But for purpose of continuity, let’s look at the next part of Barbara’s story as Mellon tells it in his article:

Repairs on the house went on, and Barbara, a girl who had hardly ever handled tools before, developed into an able do-it-yourselfer. With the help of loyal and interested friends, she hammered, sawed and painted the house back into a showplace. Her pride is a three-flue fireplace that dominates the living room. It is a reproduction of one in the American wing of the Metropolitan Museum.

Mellon finally reaches the crucial summit of Barbara’s narrative in the following paragraph:

Men and women of varied ages must have suggested the familiar narratives of the time. "A woman shouldn't be living alone renovating a house without a husband." "A magazine editor from Manhattan farming chickens?” "No one has ever opened a bookstore in a barn on some remote farm property. That’s a ridiculous idea.” But Barbara, along with an astute sense of herself and the world she inhabited, had the pronounced strength to tell her own story.

Here at Owl Pen Books on Faraway Hill, we have a handyman named Dan. He is listed in my phone as Handyman Dan, but he is also our plow guy and landscaper. He is also one of our favorite neighbors and probably the sweetest person we've met in Greenwich. Aside from helping with larger projects, he also takes the time to help me with odd two-person jobs around the property whenever I ask. He's allowed me to fix gutters, string up fallen electrical wires, move furniture, etc. He even gave me a full tutorial on operating a chainsaw. I trust his advice. When I asked Dan how he came to know how to fix the vast range of things he knows how to fix, his reply was simple. He learned by "doing." Sure, he had the benefit of being raised on a farm where a do-it-yourself ethos is ingrained in your being, but like my college-degreed forester friend, I'm sure Dan could build his house from foundation to roof. In response to my reverence for his handiness, Handyman Dan modestly claims that he couldn't play a song on the guitar, teach a class, run a bookstore, or write an essay. But I no doubt think he could. He'd have to learn by doing. Ask people for help. Be unafraid to fail. Be strong enough to change the story he's told himself about doing any of those things.

And so I'd like to say, without a hint of braggadocio, that I am working on a different story. Over the winter months, I have hung many shelves. There were drills, measuring tapes, screws, nails, saws, and sharp objects. Oh, and many trips to the hardware store. In preparation for the opening of the Owl Pen season, I painted window frames, stained posts and beams, hung artwork, built signs, and wired new lights and speakers. But, for obvious reasons, I am most proud of my shelves. They do hold and display our precious inventory of books. That's nice and all. But the best thing about these gunstock-stained boards suspended across the back wall of our cookbook room is not their mere function or aesthetic. It's a new story I remember each time I pass them.

Once I was a self-described "guy who couldn't even hang a shelf" whose wife would openly mock his home improvement shortcomings. Now I am a man who has hung many shelves that will serve their purpose in a historic bookstore for decades to come.

I am a realist. "Handy" will never be a word anyone uses to describe me. Nobody's asking me to tile a bathroom anytime soon, although I'm not ruling it out as something beyond my ability. As a conscientious student of the handy persons I live amongst, though not a probability, it's a possibility. One that could potentially lead to a new story to tell myself. At the very least, it would make for a fun essay.

To get some inspiration for the new story in your life, come on up to Owl Pen Books. We have all the books you'll never need in a place you'll never find!

A New Year for Old Books

The widow came by three times last summer. It was always on a Wednesday afternoon when we were slow. For some reason, I was the one working in the store. Sydney was out with our daughter Sally Jane, grocery shopping or going for ice cream. When July and August roll around in Washington County, and the smothering humidity brings swarms of insects that surround all parts of your face, going for ice cream is all one can do for fun. Anyway, the first time I met this widow (let's call her Dolores just because you don't hear that name enough these days), she sped up the driveway of our house in a boxy bright green SUV and tore up some of the grass in front of the store. She wasn't drunk. Dolores was in a hurry.

Before I could get her attention, waving my arms as I ran out the screen door of the bookstore to alert her that our driveway was not the store parking lot, she had thrown her green machine in park, hopped out, and begun to walk back to open her trunk, all the while yelling at her little white miniature poodle for barking at me as I approached. Though it was clear she had a lot on her mind, she moved with a forceful sense of purpose.

It occurred to me that she was the woman I had spoken to on the phone earlier that morning, the one who said she had some books for me. She had three small, open cardboard boxes. I eyed a few of the books on top. Most of the titles were about fishing and hiking in the Adirondacks. My anxiety had started to set in. I mostly rang people up and carried boxes. Book buying wasn't my area of focus. That was left to Sydney. Of the two of us, she was under the tutelage of the previous owner, Edie Brown, who advised her on what to buy from casual booksellers who ventured up our dirt road. I did overhear Edie telling Sydney once that we should always take books about local or regional history and mountaineering. "This stuff always sells," Edie said, holding up a dusty leather-bound volume about the history of Saratoga Springs.

So I assumed I'd be taking many of Dolores's books. But how much cash to offer her was my problem. What are these old books worth? How am I to know? I'm not going to look up each one on the internet only to find each is selling for seventy-five cents a piece on Amazon. After carrying all the boxes into the store, which is my primary job in our Owl Pen operation, I sat down to look through each box. Dolores stood in one spot by the door with her yipping little dog. She turned her head slowly, surveying the store, getting her bearings. Barely acknowledging her dog's bark, she seemed in a daze.

"My, you sure have a lot of books here," she said.

"Yes. They came with the place," I said as I pulled out one book on camping after another, increasingly worrying about what I should take and how much they should all add up to in the end. I didn't want to lowball this kind albeit distracted lady and insult her.

"So, are you enjoying up here? I read about you guys in the paper. You came all the way from California?"

"Yep."

"Why I on earth would you do that?" she said with a crazed smile, staring off into the dust hanging in the sunlight that shone through the barn windows.

I launched into the standard explanation that Sydney, and I are still fine-tuning to this day—something about the property, the increasing heat index in LA, the pandemic, our finances, and our quality of life. Dolores nodded. After an awkward beat, I couldn't help but cut to the chase, if only to get the stress-inducing business of book buying out of the way.

"Just so you know, I can't take all of these books from you. We only buy what we need."

"What? Oh, no, no. I'm just here to donate these books. I need to get rid of them."

"Really?" I said. I sighed quietly in relief, looking down at the sizable number of sellable products in the boxes before me on the floor. "This is quite the donation."

"Well, if you like that, there's plenty more where that came from!"

Dolores's dog began barking again. This time it didn't stop; the yipping and yapping continued all the way out to the car. I walked with her, carrying the empty boxes that had held her books, making sure to thank her a few times so she knew I was genuinely grateful for her contribution to my new livelihood. Dolores explained how her husband of forty years or so had died just ten days before. He had keeled over while they were on a walk in the neighborhood with the dog, the same dog that had been annoying me since she'd arrived. The man had just collapsed from a heart attack right there in the twilight hour on the empty village street under the greening trees amidst the burgeoning bloom of spring.

I expressed my condolences. A moment passed, a moment filled with nothing but the repetitive yelp of the dog, now aware of the squirrels and birds, choking itself on the leash held in Dolores's unsteady hand. I had a thought.

"Wait, your husband passed away last week, and you're here bringing me his books?"

"Well, there are so many, and it's really just too much clutter. Besides, what am I going to do with them?"

People often ask where we get our books and how we keep our inventory stocked. My answer always seems harsh, but it is honest and unadulterated.

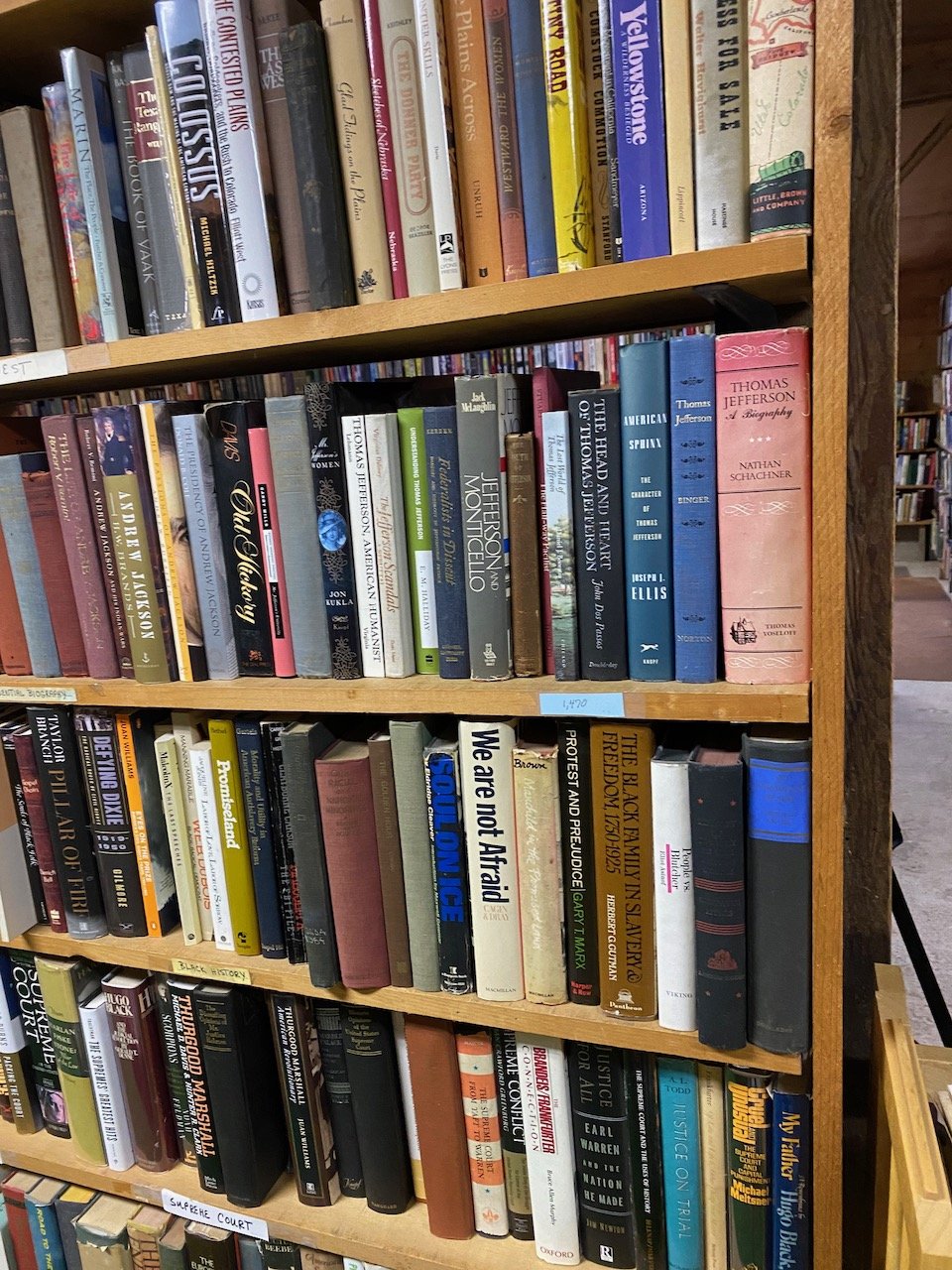

"Dead people." That's what I tell them. Sydney finds this cringeworthy. She gets embarrassed when she hears me say it, but she would never deny that it is true. Owl Pen Books stocks its shelves with the literary possessions of the deceased. There you have it. Our dark secret revealed.

Initially, I found the reality of the business, or at least this aspect, a bit morbid. And if I were to think too long about it, it would be depressing. As time goes on, however, I'm learning to accept the practice and find an inherent value in it. The easy mistake is to see our used bookstore business model as something akin to recycling. After all, books are not aluminum cans, Styrofoam cups, or plastic forks. We won't be burning them for fuel. (Although some out-of-date encyclopedia sets and Time Life collections might eventually make their way into our wood stove to make room on our dusty back stockroom shelves.)

Usually, someone passes, someone wealthy enough to have a room devoted solely to displaying books—a study, or a small library. And if they have next of kin, the readers or literary devotees of the family scour the shelves and boxes for rare and collectible editions or sentimental items they will probably place on a shelf in their home or a cardboard box in their basement, never to be read again. Then there is an estate sale we hear very little about. Collector types and online sellers might comb through the remaining books looking for scarcely found first editions or whatever they think they can get a pretty penny for. A few days after, we receive a call from someone, a family member, or a realtor, asking if we'd like to come take a few hundred books, sometimes a thousand or so. But in situations like these, I personally can't leave anything behind for them to throw in the trash. I'd rather throw the books in my trash bin and spare them the hassle of getting the local library to take them. It's the least we can do for those contributing considerably to this historic sixty-year-old business.

For most of her life, my mother was an avid reader, mostly of crime novels or the occasional Oprah's Book Club pick. She regularly checked out stacks of them from the library. When I was a kid, she finished a book every few days. But any unfamiliar person who entered our house would have no idea my mom was such a voracious reader. There were no bookshelves or decorative bound editions anywhere, not even a coffee table book in the living room. I recall two or three cookbooks in a cabinet in the kitchen. Other than that, there was the small tower of library-stamped hardcover mysteries with plastic jackets on her nightstand. To my mom, novel-length stories were a great way to relax and escape the daily grind, but books, the physical objects themselves, were just clutter, one more thing to collect dust.

When my mother sold the old house to move out east on the north fork of Long Island, her habit of frequenting the local library did not stop. The townhouse she shared with her second husband was free of shelves displaying the reading she had accomplished over the years, just the same pile under the lamplight next to her bed.

Eight years ago, my mother's husband died suddenly in the late spring. Shortly after the funeral, I went to visit her for a few weeks. What I expected to be many days of unpredictable bursts of tears and conversations bookended with fits of uncontrollable sobs turned out to be quite different. My mother seemed obsessed with removing all the clutter from her house.

Her late husband sold small antiques and collectible items he found at garage and estate sales on eBay. It was a hobby turned business he started years into his retirement. We never liked each other and had very little in common, but when he started getting into that world, I became more interested in what he had to say at the dinner table whenever I visited. One time he found a four-string tenor banjo at a garage sale in a nearby town, and it was worth thousands of dollars, enough to fund a vacation to Bermuda for him and my mother. It was like a front-row seat to a personal episode of Antiques Roadshow.

But now, all of it had to go. The rusty promotional signs for long-forgotten products, the vintage children's toys from the 50s in boxes, the World's Fair posters and guidebooks, and all of the rare knick-knacks and paraphernalia needed to be removed from the garage and attic. Boxes of "junk," as my mother referred to it, needed to be tossed or donated to Goodwill. She certainly wasn't going to be selling it online. It was all clutter. While I was going up and down the fold-out ladder to the attic, my mother shouted, "While you're up there, grab the boxes with your old report cards and sports trophies, we can throw those out too!" I ducked my head down into the garage to meet her eyes and send a disapproving look to signal that I barely thought this purging of her late husband's possessions so soon after his death was a healthy way of coping with her loss. I certainly wasn't about to let her destroy old memories of me, her son, just because a few boxes in the attic were taking up space and collecting dust. She responded, "What? You can keep what you want. I'll put it all in one box and mail it to you." And that is what she did. People do strange and drastic things when in the throes of grief.

Dolores reminded me of my mother. She even seemed around the same age. But what was most strikingly familiar to me was the tightly strung pace at which she moved, as if she had five more stops to make that day to unload all her husband's possessions. When she mentioned a whole room full of books she'd like to be rid of, I offered to come to pick them up, figuring that each trip up the winding country roads from the village would be another hassle for a widow in mourning. She politely declined, saying that she liked getting out of the house. Then she tried to sell me some cross between a kayak and a catamaran her husband had bought and used once years ago on Lake George. The annoyance I detected in her voice was the same I had felt in my mother as if she was pissed at her late-life partner for burdening her with the task of clearing out all of this "junk" from the garage. After looking up this lake boat contraption on my phone, I told her thanks but no thanks. The widow then hurried to get in her car and drive out of our parking lot down the dirt road round the bend, seeming to disappear through the woods.

Dolores returned two more times that summer, on each occasion bringing a few boxes of books we could use; each time she came with the dog. As promised, she brought at least two filled with nothing but books on canoeing. We gave her store credit, and she went to pick out one or two mystery novels, but you could tell she didn't want any more stacks accumulating in her house or to refill the shelves she'd been emptying.

Books are living objects. Yes, they collect dust. We have many dusty old ones in our store inventory. But each has had a moment spent with a person, some brief and some for entire lifetimes. Some need to be updated but serve as historical artifacts, which you might not find at your local library and certainly not at a Barnes and Noble. Often, they are reminders of personal milestones, careers, hobbies, interests, and accomplishments. (One day, I'd like to read all of War and Peace and leave it on a shelf until I die as a kind of trophy I could glance up at to instill pride or show off as an achievement to vain friends.) But when the person passes on, these beloved books become reminders of those who are no longer there. Eventually, they become just another item needing to be removed so the house can be sold. We give these books a second, third, or fourth life at Owl Pen Books. We often receive them with the previous owner Edie Brown's penciled-in price on the inside cover. Sometimes we receive small collections with a book or two bought from the original owner, Barbara Probst. What initially seemed like something oddly funny, a sign of our unconventional business model, has become a point of pride. Our store does more than sell books and records out of a barn that once housed chickens. It gives new lives and homes to works that people from our past, many long deceased, have spent considerable effort and time, sometimes lifetimes, to create. Yes, we get our books from dead people, but at Owl Pen Books, we proudly provide clutter for each new generation.

*If 2022 wasn't a year you'd like to remember, if many of the moments are just standing in the way of better times long ago, don't let them collect dust in your memory. Put them aside or trade them in for better ones in this new year. We know this can be challenging. But if we can give a new life to a two-hundred-page guide to the butter and cheese factories of the Northeastern United States published at the turn of the century—yes, we actually sold that book last year—we at Owl Pen Books believe you can breathe in vitality by letting the past die its natural death, to give birth to a more promising future. We hope you take action to enlighten yourself, to gain a fresh perspective by clearing those literal and figurative shelves, making room for knowledge and/or serenity, the kind of things found in a good old book—or a stack of them.

Best wishes for a happy 2023!

Wired for Light

It’s that time again. As the darkness of winter permeates the edges of our days, we look to our low-voltage strands of twinkle for a simulacrum of the stars. They bring us some sense of comfort, something to remind us that the sun will come again. Lights draped across aluminum gutters, tangled between tree limbs, boundlessly blinking outside warm, inviting shops on the Main Streets of villages and cities, luring us all in from the cold.

Out here in our quaint town of Greenwich, the residents celebrate the coming holiday season with their traditional tractor parade. As new additions to the community, this year marked our family’s first experience of the event. Thousands of people turn out each year in freezing temperatures to line the streets of our small town, bearing witness to a long train of tractors of various sizes, workhorses which farmers have dressed in festive colored light. There are awards for the most impressive display of sparkle. At the Tractor Parade, the particularity of lighting is of the utmost importance.

Similarly, we here at Owl Pen Books know that even in the more mundane places we routinely inhabit, the strategic and purposeful placement of light can make all the difference with regards to our overall sense of happiness and the enjoyment of our days. This is why the first change we made this past season as the new owners of Owl Pen Books was to replace the dated 1970s fluorescent lighting in the store with new strands of hanging lamp with warm, soft LED light bulbs. As fledgling proprietors, we felt a sense of obligation to leave most of Owl Pen as it had been for decades. Some features of the store—shelves, books, etc.—remain in the same places they’ve been for sixty years, since long before my wife Sydney and I were born. We chose to leave all this intact so as not to spook the devout customers. For a bookstore in a barn off a dirt road in the country to have existed for so long, the previous owners must have been doing something right. Best not touch a thing, is what we thought, at least for the first year. If it ain’t broke…

And yet, for Sydney and me, the issue of lighting was a non-negotiable matter. The long fluorescent lights that lit our store for decades suggested the less than cozy ambiance of a garage or body shop. Functionally, the bulbs managed to suck up much more energy than the modern eco-friendly LEDs while managing to fall short in providing customers with enough light to read some of the fading titles on the spines of our treasured tomes. A simple shift in lighting can make all the difference in the world. Ask any serious photographer or cinematographer. Ask a social media influencer, whatever that is…But sometimes, the “simple” lighting change, no matter how subtle, takes more effort than what feels necessary.

When we purchased Owl Pen Books, my wife and I also acquired a nearly two-hundred-year-old farmhouse. We have learned a lot about the history of our home on Faraway Hill, which stands fifty yards or so from the original Owl Pen building. The original owner, Barbara Probst, the one who dreamed up this crazy business, spent two winters living out in that tiny, converted hog pen while she renovated the main house. All her work, the projects she took on by herself, of which there were more than not, plus those jobs for which she hired skilled laborers, are well documented in her own expressive prose, found in a box of her personal unpublished essays, left on a shelf in the living room. I’ve mentioned this before in previous posts and articles. I will continue to do so. It feels like a rare gift, one that many people I tell don’t fully appreciate. How many of you have illuminating files of short memoirs detailing every aspect of the building of your home written in a charming, wry, humorous voice?

Here is what Barbara had to say about the wiring of the house and bringing our country home out of the dark ages of candle and oil lamp light:

I haunted the Niagara Mohawk Power Corp. and glory be to the U.S. Government, Rural Electrification was on the move. The boys from the power company surveyed my hermitage and, somewhat reluctantly, told me to have the house wired and then they would do their part. I noted this reluctance at the time but forged ahead on blind faith. Some ten years later when the power man came to put a bigger transformer on my entrance pole, he grinned and said: “A lot of us lost money on you ten years ago. There were darned few men on the board who thought you’d stick this thing out a year.”

But that lets out the fact I got the electricity—after two dandy chaps put wire, fuse boxes and misplaced plugs all over the place. The misplaced plugs were due to my inexperience. How could I know where furniture would be put when all I owned were two old beds, three iron frying pans and a beat-up typewriter? There’s a thousand dollars of electric wiring here and still I’m running extension cords all over the place. Ernie, the long-suffering electrician who has done my wiring since the first watt, has found me at times more trying than Okinawa. I was his first job when he got out of the army and he remembers well I kept saying, “Make everything BIG enough.” He remembers it well because I rub his nose in it every time he has to put in another fuse box. “If you’d done what I told you in the first place…,” I rail at him. H just grins and says, “Who’da believed it?”

Still, none of her writing informs us as to why, as I sit here, I must type by the light of two small lamps that sit on our farmhouse dining table, staring at the four-plug outlet powering said lamps, and why that outlet sits at belly level in the plastered wall between two original wavy glass-paned windows.

The Owl Pen will eventually need some new wiring too. But for now, the lights we strung across the ceiling of the main barn (with some # of bulbs in total) seem to be a hit with our customers. Over the six months of our first season, many regulars had kind words to say about the change. “It feels so much brighter in here!” “I can actually read all the book titles!” “It looks cleaner!” As the one who spent hours up on a ladder across every foot of the store configuring the strands and hanging the lamps, I took pride in the aesthetic change we made and the bit of ambiance it provided.

But there are always critics. Someone once told me that if you want to be a true artist of any merit, your work, though heralded by many, will be disliked by some. It is a given. Such was the case that on the final Saturday of our first season. A woman stood impatiently in our yard as customers walked about our property in the sunny last gasp of autumn. She asked if I was the new owner, then introduced herself as a longtime customer. She asked if I knew about the lights I had installed and how dangerous they were for people like herself. I didn’t know what she was talking about. Seeing my puzzled expression, she explained that she was an epileptic prone to seizures brought on by LED light rays and that because we had installed our new soft LED lights, she would no longer be able to shop in our store. Immediately, I felt awful. Immediately I became apologetic. But a healthy sense of empathy could not stifle an equally healthy sense of skepticism. I began to ask various questions about her condition. It occurred to me that nearly every modern business or public building has LED lighting. I wondered how she navigated the world. Did she not go to Target like the rest of us? She told me she did not go to many places anymore and that she had to be very careful.

There was a long back and forth, one that felt longer because I felt helpless, almost as helpless as someone with this woman’s condition. I explained she was the first person to complain about the change in lighting, and we’d received nothing but compliments. This did not affect her. I offered a compromise. I said if she came back next season, she should make sure to come on a sunny day. We would gladly turn off the lights before she entered. Somewhat appeased, she moved on to another inquiry. She wanted to know if we would sell her the original Owl Pen hog pen structure because the property she lives on had a shortage of outbuildings. Do what you will with that.

Lighting can mean everything as one can see or not see…. It can be a beat-up old tractor with some lights tossed over its chassis, or an elaborate holiday float designed with a flashy color scheme to attract villagers out into the frigid air with their lawn chairs to draw audible oohs and ahs and bursts of applause. Depends on what light you are seeing it in. Is the Owl Pen a pile of dusty old books in a barn, or is it a prestigious, historic bookstore that continues to serve a community across generations? Well, in the right kind of light, it is most certainly the latter. Barbara Probst faced critics and naysayers blind to her vision. Still, she managed to bring in the electricity that powers our homestead and lights the way for Owl Pen today. She admittedly made some mistakes and as new owners of a business, so will we. But we think Barbara would encourage our attempts to improve upon what she built. After all, how was she to predict the advent of such things as grounded three-pronged outlets, apparently dangerous but eco-friendly LED light bulbs, or an evil corporation that sells outlets and light bulbs, as well as used books?

Recently, when the sun stopped getting up before the rest of us, we were stuck with the choice between a dark kitchen in the morning or one of those long fluorescent bulbs we had replaced in the store. After a week of feeling something less than cozy when making our coffee and packing our daughter’s school lunches, I went out to the main bookstore barn and found an extra strand of those cheap but warm-looking lights in an unopened box I had forgotten about. I tore down the long, rusty fixture that provided the kind of light still likely found in an old corporate office building or even an Amazon warehouse, and hung up the temporary fixture to get us through the holidays.

Wishing you all love and light in this holiday season, the best kind of light for you. You might need the patience to wait for it to appear, like the sun or a specially decorated tractor. But in most cases, you’ll just need to move some fixtures around, and brighten some parts while dimming others. When you find the lighting that suits you, you’ll feel a deep sense of relief. Whatever the lighting choices are for you, they are bound to bother someone now or generations from now. That’s how you know they’re right.

Signs: Both Old and New

People have been complaining about our road signs. I don’t blame them. Many are small. Some are faded and unclear. For Christ’s sake, the one on Christie Road, the one by the bridge that crosses the creek, has been engulfed by overgrowth so that you can’t find it even if you know precisely where to look. These are the old signs. The new ones Sydney hand-painted in April before we opened for the year, I helped to construct those beauties out of the thinnest plywood sold at Home Depot and proudly installed them myself, pounding them like stakes into the thawing ground with a rubber mallet. Now, at the end of our first season as book barn owners, our main sign for Riddle Road, the hidden, tree-lined dirt country lane on which our store resides, falls down in the loose soil any time it rains or the wind blows too hard. Not to mention the one at the end of North Road, on the way to Cossayuna, which at the moment looks to be an arrow pointing straight up to the heavens, saying “Owl Pen This Way!”

After six months of running this business, I know one thing for sure about Barbara Probst, the founder of Owl Pen Books. I know it from speaking with some of the older generations who have come through our barn doors, and from reading her unpublished memoirs stacked in a cardboard box on a shelf in our den. She would’ve found both the customer complaints of getting lost in the Washington County countryside and our sad attempts at providing new signage hysterical. After all, what person could open a bookstore in a chicken coop, on a dirt road, amidst nothing but rolling farmland, who did not possess an acute sense of humor about most things?

My wife and I share this sense of humor. My wife, also, believe it or not, is seriously taken by astrology, and I find this funny.

When the real estate listing for Owl Pen Books showed up on her Facebook feed just over a year ago, Sydney didn’t immediately see it as a “sign.” However, after I suggested we look into what buying the beloved sixty-year-old bookstore in a barn might entail, she needed to check the stars for reassurance. The alignment of celestial bodies told her we were headed in the right direction.

She then relayed to me what they, the stars, had shown and, of course, I said, “Great! You do know that’s a bunch of nonsense, right?” To which she rolled her eyes and replied, “Whatever. You are such a Cancer.”

This is our magical dynamic, the secret of our seventeen-year relationship. She thinks our stars are aligned, and my healthy cynicism just reaffirms her superficially irrational beliefs. We are a perfect match.

As pairings go, our family is appearing to be a good fit for owning and maintaining the Owl Pen, a bookstore that an elder patron once described to me as “all the books you’ll never need, in a place you’ll never find.” This doesn’t mean we can always be the most polite stewards. It takes some degree of effort not to snap at every wayward customer who bangs open the creaky screen door to cross the threshold of our chicken coop full of books to exclaim, “well, you guys are hard to find, aren’t you!” or “we got lost a few times coming up here!” Instead, we smile and try to say something lightheartedly apologetic, but we hear this nearly every day. Though we’re grateful anyone wants to drive out on the winding roads through an array of never-ending Bob Ross landscapes and hilly farmland to our magical book barn, it is difficult to not roll our eyes when they say, “thank goodness, for GPS!” Or “Our GPS went out in some areas.” Anyone who can manage the GPS in their car also might know how to find us on the internet, either at our website, or in the various articles that have been written about us this year. Undoubtedly, in all these promotional places, it is mentioned in the gentlest of terms that our place of business is out “in the boonies.” The obscured location of our “faraway hill” would seem to be the charm of Owl Pen. I’d ask all our frustrated customers, Isn’t the absurd, off-the-grid isolation, the hidden-ness of the store, isn’t that the whole point? After all, it’s practically baked into the myth of its creation.

For over sixty years, people have been traversing the corn-covered hills of Washington County searching for Owl Pen Books. Now, as it enters its third generation of ownership it has been discovered by enough people over six decades to be granted the official status of “Historic Business” by New York State. We could take this as a sign, that under our first season of management, Owl Pen Books, a wild vision of copywriter turned chicken farmer Barbara Probst, carried forth by aspiring booksellers Edie Brown and Hank Howard, is finally receiving some long due respect. It will now be on an official list that no one will reference, on a map no one will read.

It is my opinion that Ms. Probst, an intelligent and fearlessly independent woman, opened a book farm in a barn, knowing a thing or two about people. She was operating under a kind “if you build, it they will come” model that predated Field of Dreams. Sure, she advertised in local papers and promoted her creation by all the means possible at the time long before the internet. But I’m positive that she knew, those who wanted to find Owl Pen Books would find it. They would see the tiny road signs. Those who were not that interested or didn’t care enough, would miss them. There was no worry, for these uncommitted souls were not her customers.

Sydney and I, when retelling the story of how we came to be the owners and operators of the now historic Owl Pen, always find an opportunity to insert a quick anecdote about the reaction of our friends in Los Angeles when we told them our decision to leave California, to run a bookshop in a barn in rural upstate New York. There were many who were supportive and inspired by our big move and bold life change. Some seemed envious. Others, on the other hand, for varying reasons, were vehemently opposed. And they were not shy in their naysaying. Whenever we revealed our grand plan to a loved one, it became a type of psychological test, a Rorschach of their personality. One longtime buddy of mine actually said, “If you’re looking for a life change, why don’t you sell your home, keep a condo in LA, and buy a house in the desert. You can Airbnb one of them.” He meant well with his show of concern. But he wasn’t seeing the signs we were seeing.

This continues to this day, most recently with friends and family on the east coast. An old classmate from high school came up to the store a month ago. I could see she was mesmerized by the whole property. She said she saw the potential in our two-hundred-year-old farmhouse, which we will start renovating while the store is closed for the winter. My friend wasn’t just being polite. She really got it. She could read the tiny road signs and follow the “logical” irrationality of our path.

An aunt of mine who came to visit on a rainy summer afternoon described the same house as “a bit primitive.” After taking a tour of the house and the store, I overheard her FaceTiming with my ninety-five-year-old grandmother, telling her how she could never live here. I don’t blame her. She has her own signs to follow, and they’d probably never lead her to make a home on “Faraway Hill.” My aunt may not be a regular Owl Pen customer and that is okay.

My wife and I have met many people who are more naturally suited for a lifestyle that lends itself to wandering about the countryside looking for a barn full of old books and records. These are our customers. We’ve gotten to know more than a few. It is hard to express the gratitude we feel for all the support we’ve received from the surrounding community, the generations of regular patrons of Owl Pen, as well as the adventurous new visitors who have read about us in the local newspapers and recognized it as a sign that they had to come looking for us. (We would appreciate if customers could read the sign about how to properly use our new compostable toilet before using the store outhouse known as the Chalet de Necessité… but more about that in another blog post.) The point is simply that Sydney and I appreciate all of you who have squinted hard enough to follow the signs up to see us each week from May through October. You’ve given us faith that we did read our own stars correctly. Heck, I might even start reading my daily horoscope and listening to Sydney’s astrological prescriptions…but then again, probably not.

Winter will be here soon. The signs of its approach are clear. The bitter cold and inevitable snowfall of the coming months get talked about as some boogieman that our family has yet to have encountered. Many customers say to us, “yeah, tell me how much you enjoy living here after your first winter!” Keep in mind there are many elderly people who have lived in the area their whole life, without retiring to Florida. I know this because they are our customers. (The ladies usually buy mystery novels and the gentlemen come for biographies of American historical figures and/or books on fishing.) Well, we’d like to do better than that, by presenting a monthly essay/blog for the Owl Pen. For the next six months, we will reflect on our time running the bookstore and learning the book business, while keeping you informed on exciting updates for next year. We will ruminate on country life in Washington County, and most interestingly, we will explore the vast archive of Barbara Probst’s personal narrative writing and delve deeper into the history of our beloved Owl Pen Books. Who knows, maybe we’ll just complain about the endless winter. Anyway, we hope you will give us a read each month and check in with us from time to time on our website www.owlpenbooks.com where we will be selling Owl Pen merch and carefully selected books, prints and records.